When Do Trading Cards Enter the Public Domain?

During my time writing for Cardboard Connection, the most asked questions are variations on the same theme:

When do trading cards fall in the public domain?

The answer? In typical lawyer fashion, it depends.

Legalese translation – I (sometimes) bill by the hour.

The answer “depends" because there are three parts to it: 1) an easy part, 2) a part involving research, and 3) the math part. Then, of course, there's the caveat, but we'll get to that last.

1. The Easy Part

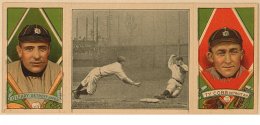

The first part of the answer is the easiest. Any work that was published before 1923 is part of the public domain. That covers a lot of ground for baseball cards, including the birth of the hobby.

2. Records and Research

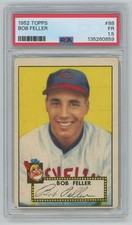

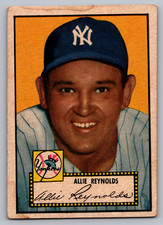

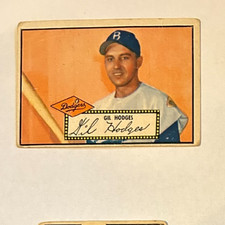

The second category of cards in the public domain (for copyright purposes) involves a little research on your end. Copyrighted works that were created between 1923 and 1963 had an initial 28-year term, which could be renewed for an additional 28 years. Despite the renewal possibility, quite a few companies blew past the deadline (some estimates are as high as 90% of copyrights were not renewed), so there is the potential to find cards in the public domain between that time span, too.

Determining this is not the easiest. The United States' Copyright Office's website only has records from 1978 until today. This would cover renewals of works from 1950 to 1963. You could also search the Copyright Office's records yourself, or even pay to have the Copyright Office conduct a search for you.

Now, when looking at the Copyright Office's website and records, you need to be careful. Just because you cannot find a copyright registration for what you are looking for does not mean it is free and clear. For example, in the Topps v. Leaf suit, Topps claims the copyright that protects a 1972 baseball rookie card resides in the book "Topps Baseball Cards: The Complete Picture Collection (A 35 Year History, 1951-1985)," which was registered by Topps in 1986. So, if you searched only for baseball cards, and entries from 1972, you might have missed it.

3. Math Magic

Turning to the third, more difficult part, we'll need to do some math. Copyrights do not last forever, although given the current statutory framework, it sure seems like they do. Under the current law, copyrights last:

- For individuals: life of the author plus 70 years.

- For works of corporate authorship: 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication (whichever is earlier).

Now we have the tools to calculate when works created after 1963 fall into the public domain. Want to try? How about this? I'll stop you now. 1963 plus 70 years or 95 years is still well past 2011. Simply, any copyrighted works created after 1963 are likely not in the public domain.

Legal translation: This is why for the rest of your life Hollywood is going to keep remaking the same movies and TV shows over and over again (Charlie's Angels, seriously?).

So, now you know the basics for determining if works are in the public domain. If it is from before 1923, it's likely free game. If it's between 1924 and 1963, quite a bit is in the public domain, but not all. And if you're looking at works after 1963, unless the author's dedicated it to the public domain, there's not much chance that it'll ever fall into the public domain.

And if you think all you'll need to do is wait 20 years or so, Congress will likely change the rules again to allow a certain media conglomerate to continue to protect its mouse.

With Every Rule, There Are Exceptions

Now time for the caveats.

Legalese translation – Like everything with the law, there is always a gray area.

Just because there might not be copyright protection for these cards, does not mean that they are free for everyone to reproduce and distribute. As the Library of Congress, who have an online gallery of more than 2,100 public domain cards, succinctly summarizes:

“While the Library of Congress is not aware of any U.S. copyright protection (see Title 17 U.S.C.) or any other restrictions in the Baseball Cards materials, there may be content protected by copyright law. Additionally, the reproduction of some materials may be restricted by privacy or other rights."

and

“Responsibility for making an independent legal assessment of an item and securing any necessary permissions ultimately rests with persons desiring to use the item."

Drafted like a true lawyer. Here's my attempt to translate another person's legalese, “Sure, we don't think there are any protections for these cards, but really, we just can't be sure. So, make your own independent determination and don't be surprised if someone comes out of the woodwork and sues you anyway."

Besides copyright, cards can be protected by a number of trademark-related claims such as trade dress, false designation of origin and player likeness. This is important because while copyrights have a limited life, trademarks do not. Basically, as long as a trademark is used in commerce, it's alive.

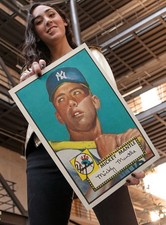

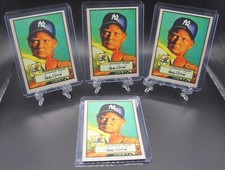

Case in point, two cards at issue in the Topps v. Leaf lawsuit are the 1952 Topps Baseball and 1956 Topps Baseball Mickey Mantle cards. From my review of the complaint, it appears these cards are not part of the copyright infringement claim. They aren't mentioned in the copyright infringement count and, from my search of the Copyright Office website, I could not find any renewals or original registrations of these cards. Likely, these cards are not protected by copyrights or Topps would have sued on them.

However, the complaint still focuses on these two cards and others under at least the false designation of origin cause of action. In other words, Topps alleges that Leaf's use of their cards would confuse consumers into believing that Topps is somehow behind or endorsing Leaf's product.

So, just because a card's copyright has expired does not mean companies will not try other avenues to protect what they believe is still their intellectual property.

This is why, even if you believe a card is actually in the public domain, it's best to hire an attorney to give you a well-reasoned legal assurance that your product is free and clear before doing anything.

Legal translation: Better be safe than sorry!

The information provided in Paul Lesko's “Law of Cards" column is not intended to be legal advice, but merely conveys general information related to legal issues commonly encountered in the sports industry. This information is not intended to create any legal relationship between Paul Lesko, the Simmons Browder Gianaris Angelides & Barnerd LLC or any attorney and the user. Neither the transmission nor receipt of these website materials will create an attorney-client relationship between the author and the readers.

The views expressed in the “Law of Cards" column are solely those of the author and are not affiliated with the Simmons Law Firm. You should not act or rely on any information in the “Law of Cards" column without seeking the advice of an attorney. The determination of whether you need legal services and your choice of a lawyer are very important matters that should not be based on websites or advertisements.

| Making purchases through affiliate links can earn the site a commission |